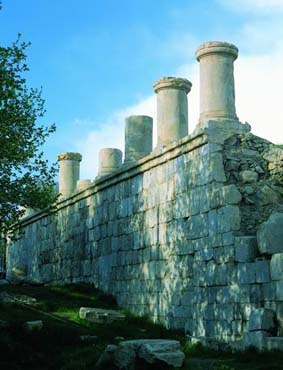

Chogha Zanbil is an ancient Elamite complex in the Khuzestan province of Iran. It is one of the few existent ziggurats outside of Mesopotamia. It lies approximately 42 km south-southeast of Dezful, 30 km south-east of Susa and 80 km north of Ahvaz.

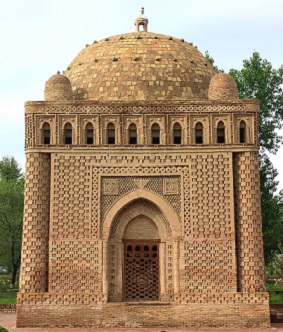

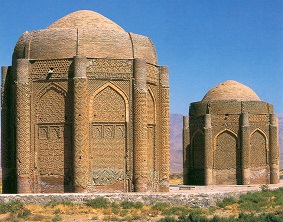

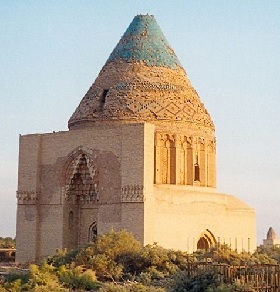

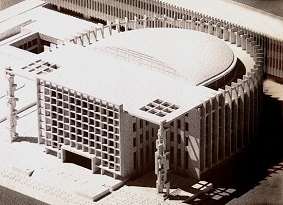

Chogha in Bakhtiari means “hill”. Choga Zanbil means ‘basket mound.’ It was built about 1250 BC by the king Untash-Napirisha, mainly to honor the great god Inshushinak. Its original name was Dur Untash, which means ‘town of Untash’, but it is unlikely that many people, besides priests and servants, ever lived there. The complex is protected by three concentric walls which define the main areas of the ‘town’. The inner area is wholly taken up with a great ziggurat dedicated to the main god, which was built over an earlier square temple with storage rooms also built by Untash-Napirisha. The middle area holds eleven temples for lesser gods. It is believed that twenty-two temples were originally planned, but the king died before they could be finished, and his successors discontinued the building work. In the outer area are royal palaces, a funerary palace containing five subterranean royal tombs.

Although construction in the city abruptly ended after Untash-Napirisha’s death, the site was not abandoned, but continued to be occupied until it was destroyed by the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal in 640 BC. Some scholars speculate, based on the large number of temples and sanctuaries at Chogha Zanbil, that Untash-Napirisha attempted to create a new religious center (possibly intended to replace Susa) which would unite the gods of both highland and lowland Elam at one site.

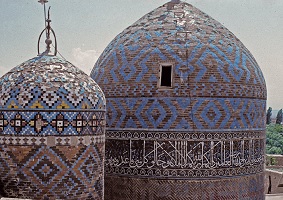

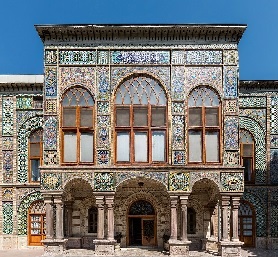

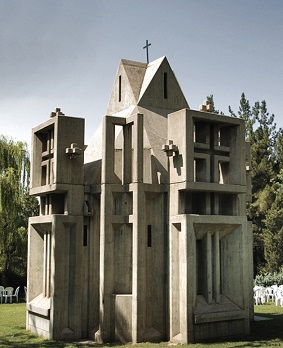

The main building materials in Chogha Zanbil were mud bricks and occasionally baked bricks. The monuments were decorated with glazed baked bricks, gypsum and ornaments of faïence and glass. Ornamenting the most important buildings were thousands of baked bricks bearing inscriptions with cuneiform characters. Glazed terracotta statues such as bulls and winged griffins guarded the entrances to the ziggurat. Near the temples of Kiririsha and Hishmitik-Ruhuratir, kilns were found that were probably used for the production of baked bricks and decorative materials. It is believed that the ziggurat was built in two stages. It took its multi-layered form in the second phase.

The ziggurat is considered to be the best preserved example in the world.[according to whom?] In 1979, Chogha Zanbil became the first Iranian site to be inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List.>