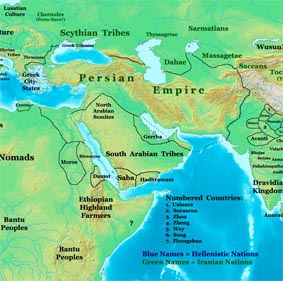

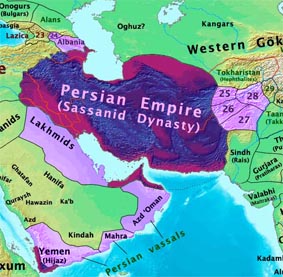

The Achaemenid Empire was the successor state of the Median Empire, expanding to eventually rule over significant portions of the ancient world. At around 500 BC this empire stretched from the Indus Valley in the east, to Thrace and Macedon on the northeastern border of Greece and eventually controlling Egypt. It was unified by a complex network of roads and ruled by monarchs (shahs), to become one of the largest and greatest empires the world had yet seen. By the 5th century BC the Kings of Persia were either ruling over or had subordinated territories encompassing not just all of the Persian Plateau and all of the territories formerly held by the Assyrian Empire (Mesopotamia, the Levant, Cyprus and Egypt), but beyond this all of Anatolia and the Armenia, as well as the Southern Caucasus and parts of the North Caucasus, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, all of Bulgaria, Paeonia, Thrace and Macedonia to the north and west, most of the Black Sea coastal regions, parts of Central Asia as far as the Aral Sea, the Oxus and Jaxartes to the north and north-east, the Hindu Kush and the western Indus basin (corresponding to modern Afghanistan and Pakistan) to the far east, parts of northern Arabia to the south, and parts of northern Libya to the south-west, and parts of Oman, China, and the UAE. In the 5th century BC, it is estimated that 50 million, or around 45% of the world population at that time lived in the Achaemenid Empire, which in terms of percentage of the world population would make it the largest empire in history.

The term Achaemenid is in fact the Latinized version of the Old Persian name Haxāmaniš (probably translating to “having a friendly mind”). Achaemenes was himself a minor 7th-century ruler of the Anshan (Ansham or Anšān) province located in southwestern Iran. It was not until the time of Cyrus the Great, a descendant of Achaemenes, that the Achaemenid Empire developed the prestige of an empire and set out to incorporate the existing empires of the ancient east.

The historical mark of the Achaemenid Empire went far beyond its territorial and military influences and included cultural, social, and religious influences as well. Many other countries adopted Achaemenid customs in their daily lives in a reciprocal cultural exchange. Cyrus founded the empire as a multi-state organisation, governed from four capital cities: Pasargadae, Babylon, Susa and Ecbatana. The Achaemenids allowed a certain amount of regional autonomy in the form of the satrapy system. A satrapy was an administrative unit, usually organized on a geographical basis. A ‘satrap’ (governor) was the governor who administered the region, a ‘general’ supervised military recruitment and ensured order, and a ‘state secretary’ kept the official records. The general and the state secretary reported directly to the satrap as well as the central government. At differing times in the empire, there were between 20 and 30 satrapies. Cyrus also created an organized army including the Immortals unit, consisting of 10,000 highly trained soldiers. Cyrus also formed an innovative postal system throughout the empire, based on several relay stations called Chapar Khaneh. The impact of Cyrus the Great’s Edict of Restoration is mentioned in Judeo-Christian texts and the empire was instrumental in spread of Persian cosmology as far east as China.

Religious toleration has been described as a “remarkable feature” of the Achaemenid Empire. The Old Testament reports that king Cyrus the Great released the Jews from their Babylonian captivity in 539–530 BC, and permitted them to return to their homeland. Cyrus assisted in the restoration of the sacred places of various cities. It was during the Achaemenid period that Zoroastrianism reached South-Western Iran, where it came to be accepted by the rulers and through them became a defining element of Persian culture. The religion was not only accompanied by a formalization of the concepts and divinities of the traditional Iranian pantheon but also introduced several novel ideas, including that of free will. Under the patronage of the Achaemenid kings, and by the 5th century BC as the de facto religion of the state, Zoroastrianism reached all corners of the empire.

Achaemenid architecture includes large cities, temples, palaces, and mausoleums such as the tomb of Cyrus the Great. The quintessential feature of Persian architecture was its eclectic nature with elements of Median, Assyrian, and Asiatic Greek all incorporated, yet maintaining a unique Persian identity seen in the finished products. Its influence pervades the regions ruled by the Achaemenids, from the Mediterranean shores to India, especially with its emphasis on monumental stone-cut design and gardens subdivided by water-courses. Achaemenid art includes frieze reliefs, metalwork such as the Oxus Treasure, decoration of palaces, glazed brick masonry, fine craftsmanship and gardening. Although the Persians took artists, with their styles and techniques, from all corners of their empire, they produced not simply a combination of styles, but a synthesis of a new unique Persian style.

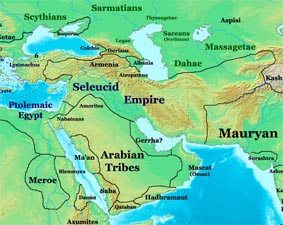

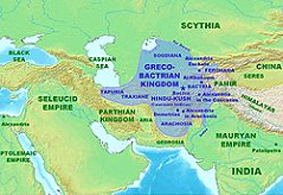

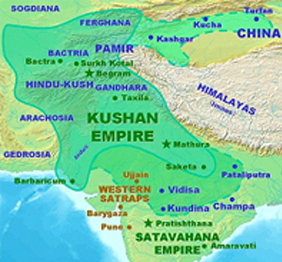

The Acahemenids fell to the invading armies of Alexander III of Macedon. Alexander defeated the Persian armies at Granicus (334 BC), followed by Issus (333 BC), and lastly at Gaugamela (331 BC). Afterwards, he marched on Susa and Persepolis which surrendered in early 330 BC. Darius III was taken prisoner by Bessus, his Bactrian satrap and kinsman who then murdered Darius III and declared himself Darius’ successor. Alexander, put him on trial and ordered his execution. Alexander generally kept the original Achaemenid administrative structure, leading some scholars to dub him as “the last of the Achaemenids”. Upon Alexander’s death in 323 BC, his empire was divided among his generals, the Diadochi, resulting in a number of smaller states. The largest of these, which held sway over the Iranian plateau, was Seleucid Empire, ruled by Alexander’s general Seleucus I Nicator. Native Iranian rule would be restored by the Parthians of northeastern Iran over the course of the 2nd century BC.