Fowler Museum, with the collaboration of Farhang Foundation is presenting a major exhibition in Los Angeles on the history of Iranian Jews from October 21, 2012 to March 10, 2013. Iran has been a mosaic of ethnicities, religions, cultures, and languages. The exhibition, called Light and Shadows: The Story of Iranian Jews is trying to show this rich and complex history of one of the world’s oldest Jewish communities, which dates back nearly 3,000 years.

Author Archives: admin

An Exhibition of works by Sadegh Tabrizi

September 25 until October 5 2012

Gallery 8 of London is to hold an exhibition of the works by Sadegh Tabrizi, a renowned Iranian artist. For the first time in over twenty years, a collection of his paintings will be brought together and exhibited. Tabrizi has been exploring calligraphic painting since the late 1950s.

Films by Abbas Kiarostami to be screened at Louvre

Tehran exhibition reveals hidden Warhol and Hockney treasures

Paintings collected with help of Iran’s last queen, Farah Pahlavi, and safeguarded in the basement of Tehran’s Museum of Contemporary Art are on show for the first time. It is the finest collection of modern art anywhere outside Europe and the US, boasting works by Jackson Pollock, Francis Bacon, Andy Warhol, Edvard Munch, René Magritte and Mark Rothko.

NY Metropolitan Museum of Art – Exhibition of Contemporary Iranian Art

March 6–September 3, 2012

This exhibition features works by three generations of Iranian artists four of whom live and work in the United States, while two continue to work in Iran. Despite their diverse modes of expression, these artworks reflect an intrinsic connection with Iran and address issues of identity, political and social concerns, gender, nostalgia, and cultural pride.

Love Came and Set the World on Fire

Love Came and Set the World on Fire

Toos Foundation: An Introduction to Iranian Mysticism >>>

The Introductory Slide Show from the Event >>>

The Mystic Poetry of the Sufis, by Said Nafisi >>>

Encyclopaedia Iranica on Mani >>>

Encyclopaedia Iranica on Hallaj >>>

Encyclopaedia Iranica on Attar >>>

Wikipedia on Sufism >>>

Wikipedia on Gnosticism >>>

Encyclopaedia Iranica Articles on Sufism >>>

Aesthetics from Classical Greece to the Present – Plotinus >>>

Love Came and Set the World on Fire

Love Came and Set the World on Fire

20th Novemebr 2011, Logan Hall, London

Introduction to Iranian History – Audio and Video

Iranian Traditional Music

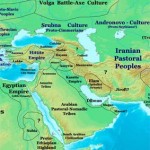

Music in Iran dates back to antiquity. Evidence of musical instruments, musical performances, singing and dancing, exist as far back as the Sumerian culture. The Elamites, centred in southwestern Iran must have carried over these musical traditions. Not much is known about that period. However, archeological evidence has revealed a number of Sumrian musical instruments that were used in Iran during the 2nd and 1st millennium BC.

Not much is known about the early Medes or Achaemenids periods either, except that music played an important role in state ceremonies, especially in religious affairs, during the Achaemenid rule. It is known that ancient Iranians had hymns which were collectively performed and that during the Achaemenids there were specially trained groups which performed these hymns. During the Parthian era, we know of the existence of groups of troubadours who were highly sought after as entertainers. The first evidence of poetry reading or singing performances accompanied by music comes from this period.

Music also played a very important role in the courts of Sassanid kings; and about its later stages we know a lot more. We know, for example, the names of various court musicians like Ramtin, Bamshad, Nakisa, Azad, Sarkash, and Barbod. We also know many of the instruments that were used like chang (harps), tanbur (lutes), ney (flutes), nayanban (bagpipes) and dayereh (drums).

Of these, Barbod (590 to 628 AD) was a highly significant court musician who developed the Persian modal system of music and modified many of the existing musical instruments and it is also said invented new ones. Indeed it is believed the word for the musical instrument Barbat (ancestor of Ouds) comes from an Arabicized version of his name. He was said to have been the inventor of the instrument. Today’s classical music tradition in Iran bears the same names of some of the modes of that era. It is, however, impossible to know if they sound the same because there is no evidence of musical notation from the Sassanid period. Barbod’s musical system consisted of 7 “modes” (known as the “khosrovani” system, named after King Khosro Parviz who commissioned the work), 30 derivative modes, “lahn” (tone), and 360 melodies named “dastan” (story). The numbers representing the number of days in a week, month and a year in the Zoroastrian calendar which was current during the Sassanid period.

Not much is known about Barbod’s musical theories on which the modal system was based, however, the writers of later periods have left a list of these modes and melodies. These names include some of epic forms such as kin-e Iraj (the Vengeance of Iraj), kin-e siavash (the Vengeance of Siavash), and Takht-e Ardeshir (the Throne of Ardeshir) and some connected with the Sassanid royal court such as Bagh-e shirin (the garden of Shirin), Bagh-e Shahryar (the Sovereign’s Garden), and haft Ganj (the seven treasures). There are also some of a contemplative or descriptive nature like roshan cheragh (bright lights). Barbod’s elaborate system indicates that he must have been the product of a rich musical tradition that went before him. His modal system is the oldest Middle Eastern musical system of which some traces still exist.

Islamic Period

Not much is known about music in Iran immediately after the Sassanid period. The Islamic era more or less ended the developments in music which were progressing at a fast pace during the previous period. Musical performances were almost banned or drastically reduced (except for military marches) and musicology in general suffered a major blow during this period. Many of the Iranian musicians of the time emigrated abroad with some ending up in the Umayyad court, the cause of their demise! Whilst Arab appointed governors of Persian provinces were very strict in enforcing musical ban on the indigenous population, the Umayaads had court musicians. The historical irony is that whilst music suffered in Iran, many Iranian musicians played a major role in developing Arabic music

The first of these was Ibrahim Al-Mawsili (742–804) whose musical family had suffered so much in the hands of the Arab governor of Fars that escaped to Kufa. Ibrahim eventually ended up at the court of Harun al-Rashid in Basra. He is said to have composed over 900 Arabic songs with Persian music. He was imprisoned many times for drinking wine but because of his popularity survived every mishap and stayed at his position in the court until his death.

His son Ishaq Al-Mawsili (767-850) became a famous composer and teacher of music. He set up a musical school in Baghdad and was well received at the Abbasid Court. It is accepted that he has had a major role in Arabic musicology although not much is known about his own work. One of his students, Zaryab (789–857 ), Abu l-Hasan Ali Ibn Nafi, became very famous in Baghdad as a poet, singer and a gifted player of the Persian barbat.

Zaryab ended up in Cordoba, at the Islamic court in Iberia. He set up a musical school that trained singers and musicians (both male and female) which influenced musical performance for at least two generations after him. He modified the Persian barbat by adding a fifth pair of strings (oud) and introduced Cordoba’s musicians to many of the Persian instruments (mainly lutes) as well as passionate songs, tunes and dances from Persia. He was a great influence on Spanish music, and is considered the founder of the Andalusian style of music. The work he did was what led to flamenco music. His inventive work on the oud also led later to the development of the Guitar.

Rudaki depicted as a blind poet, Iranian stamp

Ibn Sina

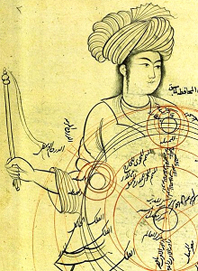

An epicyclic planetary model, from a medieval manuscript by Qotbeddin Shirazi

During the 4th century AH, Farabi (872 – 951 AD), the Persian scientist and philosopher, who also played the barbat, wrote an important book on music, kitāb al-mūsīqī al-kabīr (“The Great Book Of Music”). Although in Arabic and taken by many Arab historians to be a book about Arabic music, it is in fact about Persian music. He presents philosophical principles about music, its cosmic qualities and its influences.

Al-Farabi’s treatise on Meanings of the Intellect also dealt with music therapy, where he discusses the therapeutic effects of music. The 9th century AD saw the beginning of the breakup of Caliphate rule in Iran. Gradually a number of semi-Persian or proto-Persian kingdoms begin to develop in the Iranian parts of the Islamic empire which start promoting Persian culture. Rudaki (858 – 941), a Persian poet at the Samanid court, called the “father of Persian poetry”, and the first important poet to return to farsi language was also a chang [harp] player. He wrote a number of treaties on Persian music which have been lost.

In his wake comes Ibn Sina (980– 1037), the great Persian Physician, expert in medicine, astronomy, mathematics, philosophy and many other subjects. He also discusses music in a number of his works.

Next is Naser Khosrow (1004 – 1088) a Persian poet, philosopher and scholar. The Safarname, an account of his travels, is one of his famous works. He was well versed in all the branches of natural science, in medicine, mathematics, astronomy and astrology, in Greek philosophy and the writings of al-Kindi, al-Farabi and Ibn Sina. He was also a musician and is said to have written extensively on the subject.

After the 11th century a number of important works on Persian musicology begin to appear. The first of these is by Safi al-Din al-Urmawi (1216 – 1294) who was a renowned musician, calligrapher and writer on the theory of music. He is perhaps best known for developing in the thirteenth century the widely used seventeen-tone scale later expanded by Arab musicians to the Arabic scale of twenty-four quarter tones.

His most important works are two books on music theory, the Kitab al-Adwār and Risālah al-Sharafiyyah fi ‘l-nisab al-taʾlifiyyah. The Kitab al-Adwār is the first extant work on scientific music theory after the writings on music of Avicenna. It contains valuable information on the practice and theory of music in the Perso-Iraqi area, such as the factual establishment of the five-stringed lute (still an exception in Avicenna’s time), the final stage in the division of the octave into 17 steps, the complete nomenclature and definition of the scales constituting the system of the twelve Maghams and the six Avāz modes. It also contains precise depictions of contemporary musical metres, and the use of letters and numbers for the notation of melodies. It is the first time that this occurs in history, making it a unique work of greatest value.

By its conciseness it became the most popular and influential book on music for centuries. No other Arabic, Persian or Ottoman Turkish music treatise was so often copied, commented upon and translated into other languages. The Kitab al-Adwār was conceived as a compendium (mukhtasar) of the standard musical knowledge of its time. Al-Urmawi was in contact with the Persian scholar Nasir al-Din Tusi (1201–1274) who also left a short treatise on the proportions of musical intervals.

The next contribution came from Qotb al-Din Shirazi (1236 – 1311), a Persian poet and a Rebab player who in addition to music has made important contribution to astronomy, mathematics and medicine. He was also a Sufi thinker and wrote an important treatise on Sohrevardi’s philosophy.

The Persian poet Amir Khosro (1253-1325) is largely known for his Persian poetry but he was probably one of the most important influences on North Indian Classical Music. His writings on the Pardah system of music are a foundation stone of classical Indian music and probably explains the similarities that exist between North Indian and Iranian music. It is said he either invented the Indian Sitar or his Pardah system led directly to its invention. Sitar can make unlimited Pardah system by placing the 12-13 plectrums in various positions, thus exposing numerous potentialities.

Then comes Abd al-Qadir al-Maraghi (middle of 14th – 1435), a Persian musician and artist. Who was according to the Encyclopedia of Islam, “the greatest of the Persian writers on music“. He is known for his four works on music theory. The three surviving works are written in Persian. His most important treatise on music is the Jame’al-Alhan (Encyclopedia of Music), first written in 1405. He compiled a second edition of this work a decade later. The second major work of Abd al-Qadir is Maqasid al-Alhan (Purports of Music). The third, the Kanz al-Tu.af (Treasury of Music) which contained the author’s notated compositions, has not survived. He has also written treaties on Chinese music. He wrote songs in Persian, Arabic, Turkish and Mongolian.

Jame’al-Alhan, without any doubt is the only extant document to contain appreciable information about the modal structure of Iranian music in the pre-dastgah system. However, the definition of musical categories, the intervals of Maqam-s and their cycles, the tunning systems, the instrumentation and organological classification, and the rhythms are included in this very valuable text. For the definition of musical terms, he respectfully refers to Farabi, Ibn Sina and Safiedin Ormavi.

Recent History

Today’s formal, classical music tradition is directly linked to the music systems developed during the Safavid period (1501 – 1722). They were modified and restructured during the Qajar period into the current classical system.

Āghā Ali-Akbar Farāhāni was a renowned musician at Nasir Al-Din Shah’s court and a virtuoso tar and setar player. He is the father of two significant Iranian musicians, Mirza Abdollah and Mirza Hossein Gholi, and the paternal grandfather of another outstanding musician, Ahmad Ebadi, Mirza Abdollah’s son.

Iranian classical music relies on improvisation. Composition is based on a series of modal scales and tunes. The repertoire consists of more than two hundred short melodic movements called gusheh, which are classified into seven dastgāh (modes). Two of these modes have secondary modes branching from them called āvāz. Each gusheh and dastgah have an individual name. This whole body is called the Radif (repertoire) of which there are several versions, each in accordance to the teachings of a particular ostad (master).

Apprentices and masters, ostad, have a traditional relationship which has declined during the 20th century as music education moved to universities and conservatories. A typical performance consists of the following elements pīshdarāmad(a rhythmic prelude which sets the mood), darāmad (rhythmic free motif), āvāz (improvised rhythmic-free singing), taṣnīf (rhythmic accompanied by singing, an ode), Chahārmeżrāb (rhythmic music but rhythmic-free or no singing), reng (closing rhythmic composition, a dance tune). A performance forms a sort of suite. Unconventionally, these parts may be varied or omitted.

Towards the end of the Safavid Empire (1502-1736), more complex movements in 10, 14, and 16 beats stopped being performed. In fact, in the early stages of the Qajar Dynasty, the uṣūl (rhythmic cycles) were replaced by a meter based on the ghazal and the maqām system of classification was reconstructed into the Radif system which is used to this day. Today, rhythmic pieces are performed in beats of 2 to 7 with some exceptions. Rengs are always in a 6/8 time frame. Many melodies and modes are related to the maqāmāt of the Turkish classical repertoire and Arabic music belonging to various Arab countries, for example Iraq. This similarity is because of the exchange of musical science that took place in the early Islamic world between Persia and her neighboring countries. During the meeting of The Inter-governmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Heritage of the United Nations, held between 28 September – 2 October 2009 in Abu Dhabi, radifs were officially registered on the UNESCO List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

The classical music is vocal based. The vocalist plays a crucial role: she or he decides what mood to express and which dastgah relates to that mood. In many cases, the vocalist is also responsible for choosing the poems to be sung. If the performance requires a singer, the singer is accompanied by at least one wind or string instrument, and at least one type of percussion. There could be an ensemble of instruments, though the primary vocalist must maintain hers or his role. In some taṣnīf songs, the musicians may accompany the singer by singing along several verses. Traditionally, music is performed while seated on finely decorated cushions and rugs. Candles are sometimes lit. The group of musicians and the vocalist decide on which dastgahs and which of their gushehs to perform, depending on the mood of a certain time or situation.

Iranian classical music continues to function as a spiritual tool as it has throughout its history, and much less of a recreational activity. Compositions can vary immensely from start to finish, usually alternating between low, contemplative pieces and athletic displays of musicianship called tahrir. The incorporation of religious texts as lyrics were replaced by lyrics largely written by medieval Sufi poets, especially ghazals of Hafez and Shamsa.

Dastgah-e Shur (considered the mother of all dastgahs)

Avaz-e Abu’ata

Avaz-e Bayat-e Tork

Avaz-e Afshari

Avaz-e Dashti

Dastgah-e Homayoun

Avaz-e Bayat-e Esfahan

Dastgah-e Segah

Dastgah-e Chahargah

Dastgah-e Rastpanjgah

Dastgah-e Mahur

Dastgah-e Nava

Shiva Shafighian

Mahmoud Khoshnam

BBC Farsi report – The Iranian Opera Night: Dr. Mahmood Khoshnam (Lecturer), Pooyan Azadeh (Piano Solo), Pari Samar, Armin Mahfam and Afsane Sadeghi (Singers) >>>

Dr Raja Kamal

Dr Raja Kamal – Economics and Educations in the Fight Against Cancer >>>

Professor Susan Mayer

Professor Colm O’Muircheartaigh

Baroness Caroline Cox of Queensbury

Jamil Kharrazi

Toos Foundation-Jamil Kharrazi’s Speech at SOAS (Persian) >>>

From a poetry recital 2010 – Music by Homayoun Khosravi >>>

Jamil Kharrazi Interviews Hooshang Seyhoon (Prsian) >>>

Jamil Kharrazi Interviews Shojaeddin Shafa (Prsian) >>>

Jamil Kharrazi Interviews Pari Abasalti (Prsian) >>>

Jamil Kharrazi Interviews Farhang Farahi (Prsian) >>>

Jamil Kharrazi Interviews Reza Badei (Prsian) >>>

Jamil Kharrazi Interviews Abbas Pahlevan (Prsian) >>>

Jamil Kharrazi Interviews Jimmy Delshad (Prsian) >>>

Jamil Kharrazi Interview with Hadi Nilli, about the American University at Afghanistan (Prsian) >>>

Shiva Shafighian

Mahmoud Khoshnam

Dr Raja Kamal

Professor Susan Mayer

Professor Colm O’Muircheartaigh

Baroness Caroline Cox of Queensbury

Jamil Kharrazi

Personal Site >>>

Weblogs >>>

Lady Kharrazi at Park University >>>

Lady Kharrazi at US Command Centre General College >>>

Lady Kharrazi at the annual gala of Los Angele Ballet >>>

Ferdowsi Emrooz, No 439, Celebrities, Lady Kharrazi in Kansas City >>>

Javanan, No 1645, Kansas City Mayor Presents Lady Kharrazi with the key to the City >>>

Lady Kharrazi Is Presented with the key to Kanas City >>>

Jamil Kharrazi in Washington to Support American University in Afghanistan >>>

Jamil Kharrazi attends Global Hope Leadership Summit >>>

UNESCO Global Hope Coalition Honoring Empowering Women >>>

Salarzanan Iran Book, by Mansureh Pirnia, 2016, p372 >>>

The Harvard Committee >>>

The Harris School’d Deans International Council >>>

Buck Institute Advisory Council Memebers >>>

National University of Singapore’s International Council >>>

Iran Dance Association: Trustees >>>

Harris School Profile >>>

Shirin Ebadi Speech >>>

Woman and Democracy in the Middle East >>>

Datebook on Jamil Kharrazi Foundation >>>

The Daily Star – 2000 – Kharrazi and Ghorayeb on a new Harvard Fellowship >>>

Alwasat (Arabic) – Kharrazi-Jackson Foundations – 1998 >>>

Hello, May 1998 – Cocktails for Jackie Jackson >>>

Hello, July 1998 – Lifeline Children’s Party >>>

Hello, Oct 1998 – Haven Trust Dinner and Concert >>>

JK speech at common wealth Hall London 1998 >>>

JK speech at the event honouring Robert De Warren South Lake City USA 2009 >>>

JK speech at the event honouring Jalal Zolfonoun at Royal Festival Hall 2010 >>>

Memberships

Member of Dean’s Council, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University

Member of International Dean’s Council of Harris School, University of Chicago.

Member of International Dean’s council’s of University of Singapore

Member of the Advisory Council of The Buck Institute for Research on Aging (Novato, CA)

Sponsorships & Affiliations

Sponsor of the New Philharmonic Orchestra of London

Sponsor of Iran Dance Association

Sponsor of Artists Without Frontiers

Sponsor of the London Cultural Art Centre

Sponsor of Eastern Artists, USA

Sponsor of the humanitarian organisation of Juzourouna

Sponsor of post-graduate students from Africa and Asia

Founder of London School of Music

A Celebration of Lobat Vala

100 Years of Popular Music in Iran

History of 3000 Years of Dance in Iran

The Immortal Flowers

The Golha Project >>>

History of Classical Music in Iran

Poetry, Dance and Lyrics in the Land of Harp and Mandolins

A Celebration of Lobat Vala

Radio Kian – Naser Amini onToos Foundation’s Event: A Celebration of Lobat Vala >>>

100 Years of Popular Music in Iran

History of 3000 Years of Dance in Iran

TV Iran Farda – about Toos Foundation Events >>>

TV Tasvir Iran – Nasser Engheta interviews Jamil Kharrazi >>>

TV Tasvir Iran – Toraj Neghaban interviews Jamil Kharrazi >>>

TV Tasvir Iran – Masoud Assadollahi on Toos Foundation >>>

TV Tasvir Iran – Farhang Farahi Interviews Jamil Kharrazi 2>>>

TV Ziafat – Interview with Jamil Kharrazi >>>

The Immortal Flowers

TV Tasvir Iran – Masoud Assadollahi interviews Jamil Kharrazi and Jane Lewishon >>>

TV Tasvir Iran – Farhang Farahi interviews Jamil Kharrazi and Jane Lewishon >>>

Pars TV – Alireza Meybodi interviews Jamil Kharrazi >>>

Pars TV – Masoud Sadr interviews Jamil Kharrazi >>>

Radio Deuche Welle – Elahe Khoshnam interviews Jamil Kharrzi >>>

History of Classical Music in Iran

TV Iran Farda – about Toos Foundation Events >>>

Pars TV – Parviz Ghazisaeed interviews Jamil Kharrazi >>>

Pars TV – Alireza Meybodi interviews Jamil Kharrazi >>>

TV Andisheh – Ziafat Program – Homayoon Khosravi with Jamil Kharrazi >>>

TV Andisheh – Ziafat Program – Interview with Jamil Kharrazi >>>

Poetry, Dance and Lyrics in the Land of Harp and Mandolins

TV Iran Farda – about Toos Foundation Events >>>

Pars TV – Farhang Farahi interviews Jamil Kharazi >>>

Channel 1 – Ardavan Mofid interviews Jamil Kharrazi >>>

Pars TV – Parviz Ghazisaeed interviews Jamileh Kharrazi >>>

Andishe TV – Homayoun Khosravi interviews Jamil Kharrazi >>>

Poetry Reading by Jamil Kharrazi with music from Homayoun Khosravi >>>

Andishe TV – Ziafat – interview with Jamil Kharrazi >>>

A Celebration of Lo’bat Vala

100 Years of Popular Music in Iran

The History of 100 years of Hits in Iran 1

Persian Weekly’s report on 100 years of Hits in Iran 1 2 3

Nimrooz’s report on 100 years of Hits in Iran 1

Tehran Magazine’s report on 100 years of Hits in Iran 1 2 3

Rah-e Zendegi Magazine’s report on 100 years of Hits in Iran 1

Javanan Magazine’s report on 100 years of Hits in Iran 1 2 3

Nubahar’s report on 100 years of Hits in Iran 1

Keyhan’s report on 100 years of Hits in Iran 1 2

History of 3000 Years of Dance in Iran

The Immortal Flowers

Rangarang’s report on the Gulha program 1 2 3

Keyhan’s report on the Gulha program 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Nimrooz’s report on the Gulha program 1 2 3 4 5 6

Rooz online’s report on the Gulha program 1

Persian Weekly’s report on the Gulha program 1 2

Etela’at’s report on the Gulha program 1

Kaweh Periodical’s report on the Gulha program 1

History of Classical Music in Iran

Radio Zamaneh report on History of Classical Music in Iran 1

Persian Weekly’s report on History of Classical Music in Iran 1

Keyhan report on History of Classical Music in Iran 1234

Javanan Magazine’s report on History of Classical Music in Iran 12

Rangarang Report on Classical Music in Iran 1 2

Rah-e Zendegi Magazine’s report on Classical Music in Iran 1 2

Poetry, Dance and Lyrics in the Land of Harp and Mandolins

Bayazid Bastami

Bayazid Bastami (804-874), also known as Abu Yazid Bistami or Tayfur Abu Yazid al-Bustami, was a Persian Sufi poet born in Bastam. Bayazid’s grandfather was a Zoroastrian who converted to Islam. His grandfather had three sons, Adam, Tayfur and ‘Ali. All of them were ascetics. Abayazid was born to Tayfur. Not much is known of his childhood, but Bayazid spent most of his time in isolation in his house and the mosque.

Bayazid led a life of asceticism and renounced all worldly pleasures in order to be one with the Absolute. Bayazid became known as the first “intoxicated” Sufi. According to his peers he was both a devout moslem and a dangerous heretic. His belief in the ancient Persian idea of “unity of existence” angered the Islamic clerics in his town: “Whoever dissolves himself in God and grasps the truth he himself becomes the truth as he will become the representative of God in himself and thus finds himself within himself.” Or, “Moses desired to see God; I do not desire to see God; he desires to see me”.

Bayazid is regarded as one of the most influential mystics poets and a leading teacher of Sufism in post-Islamic Iran. Nothing has survived from his written work but references to him and his work exist in many later writings. Sufi poets such as Attar and Shams considered him a great teacher. Mohammad Ghazali (1058-1111), one of the most famous Sufi thinkers, also refers repeatedly to his debt to Bastami. The tomb of Bayazid is in Bastam near Shahroud.

Rudaki

Abu Abdollah Jafar ibn Mohammad Rudaki (858 – 941), was a Persian poet, and the first great literary genius of the Modern Persian, who composed poems in the “new” post-Islamic Persian language. Rudaki is thus considered as the founder of Persian classical literature. He is also said to have been the founder of the divan form (the typical form of the complete collection of a poet’s lyrical compositions in an alphabetical order of the rhymes, which all Persian poets use even today.

He was born in Rudak (Panjrud), a village located in Panjakent, Tajikistan. Even though most of his biographers assert that he was completely blind, some early biographers are silent about this or do not mention him as being born blind. His accurate knowledge and description of colors, as evident in his poetry, renders this assertion very doubtful.

He was the court poet to the Samanid ruler Nasr II (914–943) in Bokhara, although he eventually fell out of favour with the court after a reaction against the Ismaili sect to which it is said Rudaki belonged. Rudaki was imprisoned and tortured. Rudaki went back home where he was born and died shortly after that in poverty. He was buried there.

Mansur Hallaj

Mansur Hallaj, full name Abū al-Mughīth Husayn Mansūr al-Hallāj (858 – 922) was a Persian mystic, revolutionary writer and pious teacher of Sufism most famous for his self-proclaimed divinity, his poetry and for his execution for heresy at the orders of the Abbasid Calipha.

He was born in Toor in the Fars Province, was from a recently converted moslem family, and a Reader of the Quran. He learnt about Sufism in his youth and joined the movement. He was in contact with many of the protest movements of his time, especially Gharmatian (a radical wing of the Ismaili movement). They were mostly Iranians with Mazdaki ideas. He became a friend to Zakaria Razi the famous scientist and secular philosopher of the time and under his influence dropped out of Sufism.

Many consider him as the first Iranian thinker who set the foundations for fighting theocracy in post-Islamic Iran. His alleged crime of saying “ana al hagh” (“God is me”) was nothing more than the ancient Persian belief that god is in all of us. He was brutally executed in Baghdad after a long trial. Many later Iranian poets have devoted poems to him. Hafez says of him aprovingly: “That friend whose head made the gallows grow, his crime was making secrets glow!“

Abu-Mansur Daghighi

Abu Mansur Muhammad Ibn Ahmad Daqiqi Tusi (935/942 – 976/980), was an early Persian poet from Tus in Iran. He was a Zoroastrian convert to Islam and a court poet to Nuh II of the Samanid dynasty.

Daqiqi was a representative of the shu’ubiyah movement, which expressed the striving for independence from the Islamic caliphate by means of the glorification of native traditions and customs. He attempted to write in Persian an epic history of Iran which begun by the history of Zarathushtra and Gashtasb. He thus wrote the first versified version of the Shahnameh in New Persian. He was assassinated before he could finish it.

Only a few fragments of Daqiqi’s lyric verse remain. A large number of couplets by him (probably about a 1000 lines) were included in the epic Shahname (Book of Kings) by the Persian epic poet Ferdosi. Some scholars speculate that he wrote more, but the content was too controversial to be included in Shahname and later lost. Daqiqi’s poetry is distinguished by its picturesque quality and abundance of metaphors.

Shahid Balkhi

Abul Hasan Shahid ibn Hussain Jahudanaki Balkhi also known as Shahid Balkhi (died 935 AD) was a Persian theologian, philosopher, poet and sufi. He was a close student of the famous Persian poet Rudaki who wrote a touching elegy on the death of his favourite student. He was born in Balkh and was contemporary to Ahmed ibn Sahl al-Balkhi. He also had contacts with Zakaria Razi, the well-known Persian polymath. He wrote poems both in Persian and Arabic languages. It is also known that he was a great calligrapher.

He was living in the Samanid era so he spent most of his life in the court of Samanids and has eulogised king Nasr Ibn Ahmad Samani and his minister “Abu Abdullah Jeyhani” in his poems. Although more a Sufi than a poet, he was one of the first poets to write in Persian in the Islamic era and like Rudaki was well recieved by other poets. Rudaki, Daghighi, Manuchehri, Khaghani and Farrokhi Sistani have all written about him.

He died in Balkh, Khorasan. Only about a 100 lines of his poetry has survived.

Ferdowsi

Hakim Abolghasem Firdos Tusi more commonly transliterated as Ferdosi or Ferdowsi (940–1020) is a highly revered Persian poet. He is best known for his literary epic Shahnamehe, the national epic of Iran and related societies. Ferdosi devoted most of his life to witing it. Shahnameh was originally drafted for the Samanid rulers who were responsible for the revival of the Persian cultural traditions after the Arab invasion. Ferdosi would live to see the Samanids conquered by the Ghaznavids. The new ruler Mahmud of Ghaznavi would lack the same interest in Ferdosi’s work as that shown by the Samanids, resulting in him losing favor with the royal court. Ferdosi died in 1020 in poverty though confident that the work that he had created would last the test of time.

Written at the end of the 10th century, Shahnameh is concerned with pre-Islamic Iran, through its fictional protagonist, Rostam, a Persian hero and legend who is a greater-than-life figure (akin to Hercules) living for more than five hundred years, undergoing seven trials of strength, battling foes of man, beast, and dragon, and serving more than five Persian monarchies. Ferdosi’s Rostam is an epitome of bravery, heroism, and loyalty to the Persian throne. Rostam however is more than just a legend and a hero, in that he is constantly on the edge, and always resolute to assert that he is “his own man” able to define his own destiny and make his own choices, regardless of needs of others even those of the kings he so faithfully serves.

Farrokhi Sistani

Abul Hasan Ali ibn Julugh Farrukhi Sistani (died 1037) was a royal poet of Ghaznavids. As an ethnic Persian, he was one of the brightest masters of the panegyric school of poetry in the court of Mahmud of Ghazni.

He started his career by writing a ghasideh called ‘With a Caravan of Fine Robes’ and presented it to Asa’ad Chaghani, the vizier of Saffarid king of Sistan. This poem was so beautiful and masterful that Farrokhi was admitted to the court. The next day when the king went to his ranch to brand his new young horses, the vizier described to Farrukhi the setting of branding of horses. Farrokhi went home and based on the descriptions and without seeing the actual scene, wrote a new poem called ‘Branding Place’. The next morning he went back to the vizier and recited the poem. Vizier was so impressed that immediately took Farrokhi to the king. When this poem was recited to the king, he was so impressed that he gave 40 young horses to Farrokhi as gift.

Farrokhi was also a master in music and could play barbat and had a nice voice and could sing too. He later moved to the court of Ghaznavids, first Mahmud and then his son, Masud. Farrokhi’s divan of 9000 verses survived.

Abu Saeed AbolKheyr

Abu Saeed Abolkheyr or Abū-Sa’īd Abul-Khayr (967 – 1049), was a famous Persian Sufi who contributed extensively to the evolution of Sufi tradition. The majority of what is known from his life comes from the book Asrar al-Tohid written by Mohammad Ibn Monavvar, one of his grandsons, 130 years after his death. The book, which is an important early Sufi writing in Persian, presents a record of his life in the form of anecdotes and contains a collection of his words.

During his life his fame spread throughout the Islamic world, even to Spain. He was the first Sufi writer to widely use ordinary love poems as a way of expressing and illuminating mysticism, and as such he played a major role in the formation of Persian Sufi poetry. Also at his time the Islamic legitimacy of Sufi dance was a matter of debate among the scholars and some clerics attempted to try him and his followers on charges of un-Islamic innovations, dancing and use of poetry in public sermons, but they failed to do so because of his popularity.

Abū-Sa’īd and Ibn Sina, the Persian physician and philosopher, corresponded with one another. The first meeting is described as three days of private conversation, at the end of which Abū-Sa’īd said to his followers that everything that he could see, Ibn Sina knew, and in turn Avicenna said that everything he knew Abū-Sa’īd could see.

Rabeeh Balkhi

Rābi’a bint Ka’b al-Quzdārī, popularly known as Rabe’eh Balkhī, is a semi-legendary figure of Persian literature and was possibly the first poetess in the history of New Persian poetry. References to her can be found in the poetry of Rudaki and Attar. The longest narration of Rabia’s life and poetry is in the poem of the Elāhi-nāma (Book of the Divine) by the 12th-century Sufi poet, Farid al-Din ʿAttār.

Her biography has been primarily recorded by Zāhir ud-Dīn ‘Awfī and renarrated by Nūr ad-Dīn Djāmī. The exact dates of her birth and death are unknown, but it is reported that she was a native of Balkh in Khorāsān (now in Afghanistan). Some evidence indicates that she lived during the same period as Rūdakī, the court poet to the Samanid Emir Naṣr II (914-943).

She is said to have been descended from a royal family, her father Ka’b al-Quzdārī, a chieftain at the Samanid court, reportedly descended from Arab immigrants who had settled in eastern Persia during the time of Abu Muslim. She was one of the first poets who wrote in modern Persian, and she is, along with Mahsatī Ganjavi, among the very few female writers of medieval Persia to be recorded in history by name.

Manuchehri Damghani

Abu Najm Ahmad ibn Ahmad ibn Qaus Manuchehri aka Manuchehri Damghani, was a royal poet of the 11th century in Persia. He was from Damghan in Iran and he is said to be the first to use the form of “musammat” in Persian poetry and has the best ones too. He traveled to Tabarestan and was admitted to the court of King Manuchehr Ghabus of Ziyarid dynasty and that’s where he got his pen name.

After the death of Manucher Ghabus he went to Rey and from there he found his way to the court of Ghaznavids. He became a royal poet in the court of Sultan Shihab ud-Dawlah Mas’ud I of Ghaznavi son of Mahmud of Ghaznavi.

His poetry was mostly about nature. He also knew Arabic and is said to have had extensive knowledge of astronomy and music too. In his poetry references to these subkects are abundant. He has left behind a divan. He died in 1040 AD. His works were extensively studied by A. de Biberstein-Kazimirski in 1886.

Naser Khosro

Abu Mo’in Hamid ad-Din Nasir ibn Khusraw al-Qubadiani or Naser Khosro (1004 – 1088) was a Persian poet, philosopher, Islamic scholar and traveler. He is one of the great poets and writers in Persian literature. Safarname, an account of his travels, being his most famous work possesses a special value among books of travel, since it contains the most authentic account of the state of the Muslim world in the middle of the 11th century. He was well versed in all the branches of natural science, in medicine, mathematics, astronomy and astrology, in Greek philosophy and the writings of al-Kindi, al-Farabi and Ibn Sina; and the interpretation of the Qur’an. He had studied Arabic, Turkish, Greek, the vernacular languages of India and Sindh, and perhaps even Hebrew.

At Cairo, he became thoroughly imbued with the Shi’a Isma’ili doctrines of the Fatimids, and their introduction into his native country was henceforth the sole object of his life. He was raised to the position of dā‘ī “missionary” and appointed as the Hujjat-i Khorasan, though the hostility he encountered in the propagation of these new religious ideas after his return to Greater Khorasan in 1052 and Sunnite fanaticism compelled him at last to flee. After many wanderings he found refuge in Yamgan (about 1060) in the mountains of Badakhshan, where he spent as a hermit the last decades of his life, and gathered round him a considerable number of devoted adherents, who handed down his doctrines to succeeding generations.

Baba Taher

Baba Taher (Baba Taher Oryan) was an 11th century poet in Persian literature and a mystic thinker. Baba Tahir is known as one of the most revered and respectable early poets in Iranian literature. Most of his life is clouded in mystery. He was born and lived in Hamadan and was known by the name of Baba Taher-e Oryan (The Naked), which suggests that he may have been a wandering dervish. Legend tells that the poet, an illiterate woodcutter, attended lectures at a religious school, where he was not welcomed by his fellow-students. The dates of his birth and death are unknown. One source indicates that he died in 1019. If this is accurate, it would make Baba Taher a contemporary of Ferdosi and Ibn Sina (Avicenna) and an immediate precursor of Omar Khayyam.

Baba Tahir poems are recited to the present day all over Iran. Baba Tahir’s poems are of the do-bayti style, a form of Persian quatrains, which some scholars regard as having affinities with Middle Persian verses. Classical Persian Music is based on Persian literature and Baba Tahir’s poems are the weight that carries a major portion of this music. Baba Tahir’s poetry is the basis for Dastgahe Shoor and in particular the Gooshe s of Dashtestani, Choopani and Deylaman. Attributed to him is also a work by the name Kalemat-e qesaar (catch phrases), a collection of nearly 400 aphorisms in Arabic,

His tomb, designed by Mohsen Foroughi, is located near the northern entrance of the city of Hamadan in Western Iran.

Ghatran Tabrizi

Abū-Mansūr Qatrān-i Tabrīzī (1009–1072), was a royal Persian poet. He was born in Sahar near Tabriz and was the most famous panegyrist of his time in Iran. He would identify his ancestry from Gilan and from the Dehqan class. His work has aroused the interest of historians, for in many cases Qatran has perpetuated the names of members of regional dynasties in Azerbayjan and the Caucasus region that would have otherwise fallen in oblivion.

Qatran’s poetry follows in the wake of the poets of Khorasan and makes an unforced use of the rhetorical embellishment. He is one of the first poets after Farrokhi to try his hand at the Ghasidehi (ode) form. Qatran’s ghasidehs on the earthquake of Tabriz in 1042 has been much praised and is regarded as a true masterpiece .

In his Persian divan of 3000 to 10000 couplets, Qatran praises some 30 patrons. He is not to be confused with another Persian author: Qatran of Tirmidh, who wrote the Qaus-nama one hundred years later.

Khajeh Abdollah Ansari

Abu Ismaïl Abdullah ibn Abi-Mansour Mohammad or Khajeh Abdollah Ansari of Herat (1006–1088), also known as Pir-e Herat (sage of Herat) was a famous Persian Sufi who lived in the 11th century in Herat. One of the outstanding figures in Khorasan in the 11th century: a commentator of the Ghoran, traditionalist, polemicist, and spiritual master, known for his oratory and poetic talents in both Arabic and Persian.

He practiced the Hanbali fiqh, one of the four Sunni schools of law or jurisprudence. His shrine, built during the Timurid Dynasty, is a popular pilgrimage site.

He wrote several books on Islamic mysticism and philosophy in Persian and Arabic. His most famous work is “Munajat Namah” (literally ‘Litanies or dialogues with God’), which is considered a masterpiece of Persian literature. After his death, his students and disciples compiled his teachings about the Tafsir of Quran, and named it “Kashful Asrar”. This is the best and lengthiest Sufi Tafsir of Quran, being published several times in 10 volumes.

Masud Sa’d Salman

Mas’ud-i Sa’d-i Salmān was an 11th century Persian poet of the Ghaznavid empire who is known as the prisoner poet. He was born in 1046 in Lahore to wealthy parents from Hamadan, and his father Sa’d bin Salman was a great Persian ambassador who was sent to India by the Ghaznavids. Masud was born there and he was highly learned in astrology, calligraphy, and Persian and Arabic literature (he also knew the Indian languages).

In 1085, he was thrown into prison. He was released in 1096, when he returned to Lahore continued political changes resulted in another prison stay of 8 years. Most of his best poems were written in prison. He is therefore also known as the prison poet. His poems are beautiful and melancholic. Most of his works are written in the ghasideh form but he also has many quatrians. During one of his prison stays, he wrote the Tristia, a celebrated work of Persian poetry. He was in touch with some of the Persian Poets of the time, including Sanaii.

Sanai

Hakim Abul-Majd Majdūd ibn Ādam Sanā’ī Ghaznavi was a Persian Sufi poet who lived in Ghazna, in what is now Afghanistan during the 11/12th century. He was connected with the court of the Ghaznavid Bahram-shah who ruled 1118-1152. It is said that once when accompanying Bahramshah on a military expedition to India, Sanai met the Sufi teacher Lai-khur. Sanai quit Bahramshah’s service as a court poet even though he was promised wealth and the king’s daughter in marriage if he remained.

He wrote an enormous quantity of mystical verse, of which The Walled Garden of Truth or The Hadiqat al Haqiqa is his master work and the first Persian mystical epic of Sufism. Dedicated to Bahram Shah, the work expresses the poet’s ideas on God, love, philosophy and reason. Sanai taught that lust, greed and emotional excitement stood between humankind and divine knowledge. Love and a social conscience are for him the foundation of religion; mankind is asleep, living in a desolate world. To Sanai common religion was only habit and ritual. For close to 900 years. Sanai’s poetry had a tremendous influence upon Persian literature. He is considered the first poet to use the qhasidah (ode), ghazal (lyric), and the masnavi (rhymed couplet) to express the philosophical, mystical and ethical ideas of Sufism. Rumi acknowledged Sanai and Attar as his two primary inspirations, saying, “Attar is the soul and Sanai its two eyes, I came after Sanai and Attar.”

Khayyam

Omar Khayyám (1048–1131) was a Persian mathematician, astronomer, philosopher and poet. He also wrote treatises on mechanics, geography, and music. Born in Nishapur, at a young age he moved to Samarkand and obtained his education there, afterwards he moved to Bukhara and became established as one of the major mathematicians and astronomers of the medieval period. He is the author of one of the most important treatises on algebra credited with a geometric method for solving cubic equations. He also contributed to a reform of the Persian calendar.

His significance as a philosopher and teacher, and his few remaining philosophical works, have not received the same attention as his scientific and poetic writings. Many sources have testified that he taught for decades the philosophy of Ibn Sina in Nishapur. He is buried there.

Outside Iran and Persian speaking countries, Khayyám has had a major impact through the translation of his quatrains (rubaiyat) and popularization by other scholars. The most influential of all was Edward FitzGerald (1809–83) who made Khayyám the most famous poet of the East in the West through his celebrated translation of Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám.

Mahsati Ganjavi

Mahsati Ganjavi (1089 – 1159) was a 12th century Persian poet. As an eminent poet, she was composer of quatrains (ruba’is). Originated from Ganja (Azarbayejan), she was said to have associated with both Omar Khayyam and Nezami.

She was a poet laureate to the courts of Sultan Muhammad I (1118-1131) and his uncle Sultan Sanjar (1131-1157). Her alleged free way of living and her verses have stamped her as a Persian Madame Sans-Gêne. Her purported love affairs are recounted in the works of Jauhari of Bukhara.

No details about her life are documented except that she was highly esteemed at the court of sultan Sanjar. It is also known that Mahsati was persecuted for her courageous poetry condemning religious obscurantism, fanaticism, and dogmas.

Her only works that have come down to us are philosophical and love quatrains, glorifying the joy of living and the fullness of love. Approximately 60 quatrains of her are found in the Nozhat al-Majales. A monument to her was erected in Ganja in 1980.

Nezami

Nezami Ganjavi whose formal name was Niẓām ad-Dīn Abū Muḥammad Ilyās ibn-Yūsuf ibn-Zakkī, is considered the greatest romantic epic poet in Persian literature, who brought a colloquial and realistic style to the Persian epic. His heritage is widely appreciated and shared by Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Iran, and Tajikistan. He was born in Ganjeh, Azarbayejan.

Because Nezami was not a court poet, he does not appear in the annals of the dyansties. Tazkerehs, which are the compilations of literary memoirs that include maxims of the great poets along with biographical information and commentary of styles, refer to him briefly. Much of this material in these Tazkerehs are based on legends, ancedotes, and hearsays. Consequently, few facts are known about Nezami’s life, the only source being his own work, which does not provide much information on his personal life.

Nezami’s favorite pastime was reading Ferdosi’s Shahnameh. Nezami advises the son of the Shirvanshah to read the Shahnameh and to remember the meaningful sayings of the wise. Nezami has used the Shahnameh as a source in his three epics of “Haft Paykar”, “Khosro and Shirin” and “Eskandar-nameh”.

Khaghani Shirvani

Khāqāni or Khāghāni (1121 – 1190) was a Persian poet. He was born in the historical region known as Shirvan, under the Shirvanshah (a vassal of the Seljuq empire) and died in Tabriz, Iran. Khaqani (real name, Afzaladdin Badil ibn Ali Nadjar) was born into the family of a carpenter. In his youth, Khaghani wrote under the pen-name Haqai’qi (“Seeker”). After he had been invited to the court of the Shirvanshah, he assumed the pen-name of Khaghani.

He soon fled the life of a court poet and set off on a journey about the Middle East. His travels gave him material for his famous poem Tohfat-ul Iraqein (A Gift from the Two Iraqs), the two Iraqs being ‘Persian Iraq’ (western Iran) and ‘Arabic Iraq’ (Mesopotamia). This book also supplies us with a good deal of material for his own biography. He also wrote the famous Ode to the Portals at Mada’in beautifully painting his sorrow and impression of the remains of the ancient Persian Palace at Madaen. On return home, Shah Akhsitan gave order for his imprisonment. It was in prison that Khaqani wrote one of his most powerful anti-feudal poems called Habsiyye (Prison Poem). Upon release he moved with his family to Tabriz where fate dealt with him one tragic blow after another: first his young son died, then his daughter and then his wife. Khaqani composed moving elegies for all three most of which have survived and are included in his divan. Khagani died in Tabriz and is buried at the Poet’s Cemetery in Surkhab Neighbourhood of Tabriz.

Anvari

Anvari (1126–1189), full name Awhad ad-Din ‘Ali ibn Mohammad Khavarani was one of the greatest Persian poets. He was born in Abivard of (now in Turkmenistan) and died in Khurasanian Balkh, now in Afghanistan, and studied science and literature at the collegiate institute in Toon (now Ferdows, Iran), becoming a famous astronomer as well as a poet. His references to musical terms in his poetry reval also an expertise in music too.

His surviving divan of poems contain some 15,000 lines. Anvari’s poems were translated into English in 1789, and Cambridge History of Iran calls him “one of the greatest figures in Persian literature”. Despite their beauty, his poems often required much help with interpretation, as they were often complex and difficult to understand.

Attar

Abū Hamīd bin Abū Bakr Ibrāhīm (1145-1221); better known by his pen-names Farīd ud-Dīn Attār, was a Persian mystic poet, theoretician of Sufism, and hagiographer from Nīshāpūr who had an abiding influence on Persian poetry and Sufism. Information about Attar’s life is rare. He is mentioned by only two of his contemporaries, `Awfi and Tusi. However, all sources confirm that he was from Neyshapur, a major city of medieval Khorasan (now located in the northeast of Iran), and according to `Awfi, he was a poet of the Seljuq period. It seems that he was not well known as a poet in his own lifetime, except at his home town, and his greatness as a mystic, a poet, and a master of narrative was not discovered until the 15th century.

Attar was the son of a prosperous chemist, receiving an excellent education in various fields. He practiced the profession of pharmacy and personally attended to a very large number of customers. Eventually, he abandoned his pharmacy store and traveled widely – to Baghdad, Basra, Kufa, Mecca, Medina, Damascus, Khwarizm, Turkistan, and India, meeting with Sufi Sheykhs – and returned home promoting Sufi ideas. His talent for perception of deeper meanings behind outward appearances enables him to turn details of everyday life into illustrations of his thoughts. He possessed an inexhaustible fund of thematic and verbal inspirations which is reflected in all his poetry. He himself says when he composed his poems, more ideas came into his mind than he could possibly use.

Afzal al-Din Kashani

Afzal al-Din Kashani, Baba Afzal, was a Persian poet and philosopher. Several dates have been suggested for his death, with the best estimate being around 1213-1214. The information on his life is scanty and few. His writing portray a disdain for officials of his time and he is said to have once been imprisoned by the local governor on trumped-up charges of practicing sorcery. His tomb located in the village Maraq, northwest of Kashan, is still a place of pilgrimage.

His influence on later thinkers has not been investigated however his works which are clearly and beautifully written were probably a source of inspirtation for philosophical writings in both Arabic and Persian. For his part, he follows the philosophical and logical terminology of Avicenna while most his works evoke a visionary aura in spite of their philosophical and logical exactitude. Besides his poetry, 54 works of prose in varying length have survived.

Around 500 quatrains are ascribed to him. Some of the themes include warnings about the futility of involvement with the things of the corporeal world, the correspondence between microcosm and macrocosm, and self-knowledge as the goal of human existence.

Saadi

Abū-Muḥammad Muṣliḥ al-Dīn bin Abdallāh Shīrāzī better known by his pen-name as Saadi, was one of the major Persian poets of the medieval period. He is not only famous in Persian-speaking countries, but widely quoted in western sources. He is recognized for the quality of his writings, and for the depth of his social and moral thoughts.

A native of Shiraz, his father died when he was an infant. Saadi experienced a youth of poverty and hardship, and left his native town at a young age for Baghdad to pursue a better education. As a young man he was inducted to study at the famous an-Nizzāmīya center of knowledge (1195–1226), where he excelled in Islamic Sciences, law, governance, history, Arabic literature and theology. Saadi witnessed first-hand accounts of Baghdad’s destruction by Mongol Ilkhanate invaders led by Holaku Khan in 1258. He was later captured by Crusaders at Acre where he spent 7 years as a slave digging trenches.

When he reappeared in his native Shiraz he was an elderly man. Saadi was not only welcomed to the city but was respected highly by the ruler. In response, Saadi took his nom de plume from the name of the local prince, Sa’d ibn Zangi and wrote a number of poems in praise of the ruling house. The remainder of Saadi’s life seems to have been spent in Shiraz.

Shams Tabrizi

Mohammad Ibn Ali Malekdad Tabrizi, known as Shams Al Din (Shams Tabrizi) is a renouned Persian Sufi poet. He is credited with being the spiritual mentor of Molavi (Rumi). He studied with masters Shams Khoyee (or Khonjee), pir Sajasi and Sale Baf. From his works it is clear he has also been influenced by a number of great thinkers of his time. He himself mentions, Shahab Hariveh, Fakhr Razi, Ohad Al Din Kermani and Ibn Arabi. Not much is known about his life until Maghalate Shams (Shams Articles) was discovered. The oldest documents we had before were written by Soltan Valad (son of Molavi) and Sepahsalar an old friend of Molavi who says “no living soul knew much about Shams, he hid his fame and always covered himself in a shroud of secrets”.

Shams’s entery to Konya and his meeting with Molavi is one of those legendary stories of Iranian culture. The effect of Shams was such that Molavi, a well respected theologian was turned into a distressed person in love. This mysterious old man made the son of the chief clerics to turn away from his teaching duties and join a circle of mystic dance, sama. The peers and followers of Molavi at the theological school become enemies of Shams and the animosities become so public that Shams is forced to leave town. On Molavi’s insistence and the promise of peace by the enmies he is invited back to Konya, but soon the enmities resume. One night sitting in Molavi’s residence he is called to the door. After this he disappears. And from here on the story is not clear. Did they just murder him and throw him in a well nearby (which is the most likely event and the more accepted version today) or did he really disappear. There is no evidence to prove that any of his reputed musoleums in Turkey, Iran or Pkistan have actually anything to do with Shams.

The famous Divan Shams, allegedly written by Molavi after Shams’s disappearance was published 70 years after the death of Molavi. There is no proof that the more than 3000 ghazals in this Divan were written by Molavi or indeed written by one person. At least 5 different styles of poetry can be detected in this collection. Indeed some of the poetry (given their philosophical content) probably belongs to Shams himself.

Owhad-al-din Kermani

Sheikh Owhad-al-din Hamed abu-al Fakhr Kermani born in Bardsir, Kerman (probably 1173) was a mystic poet. At the age of 16 he migrated to Baghdad and studied and later taught there; until he dropped everything and became a wanderring sufi. He lived in what is now Turkey for many years but returned to Baghdad ans is burried there.

He was influenced by the ideas of Ibn Arabi. He joined the followers of Shams al-din Sajjasi (also one of the teachers of Shams Tabrizi). It is said he was a contemporary of Shams Tabriz and had met him in Damsqus. From all accounts, however, the two had entirely opposing views.

There are over 2000 of his quatrains (robaiiyat) that have survived.

Molavi

Jalāl ad-Dīn Muḥammad Balkhī, also known as Rūmī and popularly known as Mowlānā or more commonly as Molavi (1207–1273), was a 13th-century Persian poet, theologian, and Sufi mystic. Rūmī is a descriptive name meaning “the Roman” since he lived most of his life in an area called Rūm (present-day Turkey) because it was once ruled by the Eastern Roman Empire.

He was born in Balkh, at that time part of the province of Khorasan. His father decided to migrate westwards for fear of the impending Mogul invasion. Rumi’s family traveled west, first performing the Hajj and eventually settling in the Anatolian city Konya (capital of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum), as a result of the insistent invitation of ‘Alā’ ud-Dīn Key-Qobād, ruler of Anatolia who wanted Rumi’s father Bahā ud-Dīn Walad to head the theological school in Konya, A position which after his father’s death was occupied by Rumi. This was where he lived most of his life, and where he composed one of the crowning glories of Persian literature, Masnavi, on which he spent the last 15 years of his life and which has profoundly affected the Persian culture and beyond. A book in which even today people find messages of peace and liberation in its stories. Molavi himself said: “I did not write Masnavi so that you place it on the mantelpiece but so that you stand on it to rise higher. It is the ladder to the truth but not one to be taken on shoulders wandering from city to city.”

Rumi’s life was completely changed after his famous meeting with a mystic, Shams Tabrizi on 15 November 1244. After a few weeks with Shams, Rumi was transformed from an accomplished Islamic theologian, teacher and jurist into an ascetic. Shams had travelled throughout the Middle East searching and praying for someone who could “endure my company”. Shams was at first forced to leave Konya and then eventually murdered on his return to Konya by those who wanted to end this friendship with Rumi. On the night of 5 December 1248, as Rumi and Shams were talking, Shams was called to the back door. He went out, never to be seen again.

Rumi’s love for, and his bereavement at the disappearance of Shams found their expression in an outpouring of lyric poems. It is said Masnavi and Divan-e Shams-e Tabrizi were written in this period. Although the latter published many years after the death of Rumi probably contains many poems from Shams himself or added later by others. Rumi’s works were written in the Persian language but occasionally he also used Turkish, Arabic, and Greek in his verse. Molavi was part of a new Persian literary renaissance which started in Khorāsān and by the 10th century it reinforced the Persian language as the preferred literary and cultural language in the Persian Islamic world.

Fakhr-al-Din Iraqi

Fakhr al-dīn Ibrahīm (June 10, 1213 – 1289) is one of the great Sufi writers and poets. He was born in Hamadan but during his lifetime he spent many years in Multan, (present day Pakistan) as well as Konya and Toqat (in present day Turkey).

Iraqi was highly educated in both theology and literary disciplines and not only knew Islamic theology but also Persian and Arabic literature. By the time he was seventeen Iraqi begun to teach others. Soon after he began teaching he met a group of wandering dervishes and decided to join them. The group traveled to Multan where he would eventually be in the service of Shaykh Baha’uddin Zakariyya’ Multan who was the head of the Suhrawardi Order.

Iraqi travelled and stayed in Konya too where he met with Molavi. He eventually ended up in Damascus where he would eventually died. Lama’at (or Divine Flashes) is the best known of ‘Iraqi’s writings and was written during his time in what is now present day Turkey. It is in the ‘language of love’ genre within Sufi writings and it takes an interesting view on how one should view the world. Unlike others before him Iraqi viewed the world as a mirror which reflected the Absolute and not as a “veil” which must be lifted.

Awhadi Maraghai

Awhaduddin Awhadi Maragheie (also written Ohadi) (1271–1338) was a Persian poet from the city Maragha in Iran. He is usually surnamed Maraghei, but also mentioned as Awhadi Esfahani because his father came from Isfahan and he himself spent part of his life there. He first chose the pen-name Ṣāfī, but changed it to Awhadi after becoming a devotee of the school of the famous mystic Shaikh Auhaduddin Kermani.

Ohadi has a divan of 8000 verses which consists of the Persian poetic forms Ghasides, Ghazals, Tarji’bands and Quatrains. The Qasidas are in praise of Abu Said and his Vizir, Ghiyath al-Din, the son of Rashid al-Din Fazzlah. His other poems play on various themes including mysticism, ethnics and religious subjects.

In addition to his divan, he has left two important Persian works in Mathnavi. The Dah-nama or Manteq al-Oshaaq consists of 600 verses and was completed in 1307 for Wajih Al-din Yusef, the grandson of the famous Nasir al-Din Tusi. His most important and well known work was the Masnavi Jam-i Jam also called Jam-e-Jahanbin (“The mirror of the universe”). He is burried in Maraghe.

Amir Khosrow Dehlavi

Ab’ul Hasan Yamīn ud-Dīn Khusrow (1253-1325 CE) better known as Amīr Khosrow was a musician, scholar and poet. He was an iconic figure in the cultural history of the Indian subcontinent. A Sufi mystic and a spiritual disciple of Nizamuddin Auliya of Delhi, Amīr Khusrow was not only a notable poet but also a prolific and seminal musician. He wrote poetry primarily in Persian, but also in Hindavi.

He is regarded as the “father of qawwali” (the devotional music of the Sufis in the Indian subcontinent). He is also credited with enriching Hindustani classical music by introducing Persian and Arabic elements in it, and was the originator of the khayal and tarana styles of music. The invention of the tabla is also traditionally attributed to Amīr Khusrow.

Amir Khusrow was prolific in tender lyrics as in highly involved prose and could easily emulate all styles of Persian poetry which had developed in medieval Persia, from Khāqānī’s forceful qasidas to Nizami’s khamsa. He used only 11 metrical schemes with 35 distinct divisions. The verse forms he has written in include Ghazal, Masnavi, Qata, Rubai, Do-Beyti and Tarjiband. His contribution to the development of the ghazal, is particularly significant.

Khwaju Kermani

Khwaju Kermani was a famous Persian poet and Sufi mystic born in Kerman in 1290. He was associated with the Persian sufi master Sheykh Abu Esshagh Kazeruni, the founder of the Morshediyyeh order. He is also know as Nakhlband.

When he was young, he visited Egypt, Syria, Jerusalem and Iraq. He also performed the Hajj in Mecca. One purpose of his travels is said to have been education and meeting with scholars of other lands. He composed one of his best known works, Homāy o Homāyun in Baghdad. Returning to Persian lands in 1335, he strove to find a position as a court poet by dedicating poems to the rulers of his time, such as the Il-Khanid and the Mozaffarid rulers.

He was a prolific writer and much of his work has survived (amlost all in Persian). His ideas are said to have had a major influence on Hafez. He was given the title of khallagh-ol ma’ani (creator of meaning). He passed away around 1349-52 in Shiraz, Iran, and his tomb in Shiraz is a popular tourist attraction today.

Mahmud Shabistari

Mahmūd Shabestarī (1288 – 1340) is a celebrated Persian Sufi poets of the 14th century. He was born in the town of Shabestar near Tabriz. He became deeply versed in the symbolic terminology of Ibn Arabi.

His most famous work is a mystic text called The Secret Rose Garden (Gulshan-e Rāz) written about 1311 in rhyming couplets. This work was written in response to seventeen queries concerning Sufi metaphysics posed to “the Sufi literati of Tabriz” by Rukh Al Din Amir Husayn Harawi. It was also the main reference used by François Bernier when explaining Sufism to his European friends in the 17th century.

Other works include The Book of Felicity (Sa’adat-nāme) and The Truth of Certainty about the Knowledge of the Lord of the Worlds (Ḥaqq al-yaqīn fi ma’rifat rabb al-‘alamīn). The former is regarded as a relatively unknown poetic masterpiece written in khafif meter, while the later is his only remaining work of prose.

Seyf Farghani

Molānā sayf-edin Muhammad Farghānī (Known as Seyf Farghaani) was a 13th-14th century Persian poet and sufi. He was born in Farghāneh a city in Transoxiana and was burried in Aqsara.

Obeyd Zakani

Nezam od-Din Ubeydollah Zâkâni was a Persian poet and satirist of the 14th century from the city of Qazvin. He studied in Shiraz, Iran under the best masters of his day, but eventually moved back to his native town of Qazvin. He however preferred Shiraz to Qazvin, as he was a court poet in Shiraz for Shah Abu Ishaq, where a young Hafez was present as well.

His work is noted for its satire and obscene verses, often political or bawdy, and often cited in debates involving homosexual practices. He wrote the Resaleh-ye Delgosha, as well as Akhlaq al-Ashraf (“Ethics of the Aristocracy”) and the famous humorous fable Masnavi Mush-O-Gorbeh (Mouse and Cat), which was a political satire. His non-satirical serious classical verses have also been regarded as very well written, in league with the other great works of Persian literature.

He is one of the most remarkable poets, satirists and social critics of Iran (Persia), whose works have not received proper attention in the past. His books are translated into Russian, Danish, Italian, English, and German.

Emad Faghih Kermani

Emad Faghih Kermani is a Sufi poet a contemporary of Hafez and noted by him. His father was a well known Sufi thinker in kerman and had built a khaneghah there. After his death, Emad took over the running of the khaneghah.

He started writing poetry from an early age and was considered a very skilful poet and well received at the court of mozaffarids. Of his works, in addition to his divan of poems, 5 masnavis have also survived. He died in Kerman and was burried there.

Hafez

Khwāja Šamsu d-Dīn Muḥammad Hāfez-e Šhīrāzī, known by his pen name Hāfez (1325 – 1389) was a Persian lyric poet. His collection of ghazals are to be found in the homes of most Iranians, who learn his poems by heart and use them as proverbs and sayings to this day. His life and poems have been the subject of much analysis, commentary and interpretation, influencing post-Fourteenth Century Persian writing more than any other author.

Themes of his ghazals are the beloved, faith, and exposing hypocrisy. His influence in the lives of Iranians can be found in Hafez-readings, frequent use of his poems in Persian traditional music, visual art and Persian calligraphy. His tomb in Shiraz is a masterpiece of Iranian architecture and visited often. Adaptations, imitations and translations of Hafez’ poems exist in all major languages.

The question of whether his work is to be interpreted literally, mystically or both, has been a source of concern and contention to scholars. This confusion stems from the fact that, early in Persian literary history, the poetic vocabulary was used by mystics who believed that the divine could be better approached in poetry than in prose and that the specifically Persian as opposed to official Islamic beliefs and value systems could best be hidden in poetry. In composing poems of mystic content, they imbued every ordinary word and image with mystical undertones, thereby causing mysticism and lyricism to essentially converge into a single tradition.

Shah Nimatullah Wali

Shah Nimatullah Wali or Ne’matollah Wali, was an Islamic scholar and a Sufi poet from the 14th and 15th centuries. Descended from the Ismaili Imam Muhammad ibn Ismail, Ni’matullah was the Qutb of a Sufi order after his master Sheikh Abd-Allah Yafae. Today there is a Sufi order Nimatullahi that considers him its founder.

Born in Aleppo, Syria, he travelled widely through the Muslim world, learning the philosophies of many masters, but not at first finding a personal teacher he could dedicate himself to. During this time, Ni’matullah also studied the writings of the great Sufi philosopher and mystic Ibn al-‘ Arabi. Ni’matullah met Abdollah Yafe’i in Mecca and subsequently became his disciple. He studied intensely with his teacher for seven years until, spiritually transformed, he was sent out for a second round of travels, this time as a realized teacher.

Ni’matullah temporarily resided near Samarkand, along the great Central Asian Silk Road. It was here that he met the conqueror Tamerlane, but to avoid conflict with the worldly ruler, he soon left and eventually settled in the Persian region of Kerman. His poetry belongs to this period. He has a left a Persian Language Diwan (poetry). His shrine is in nearby Mahan.

Abu Ashagh Atameh

Abu Ashaghe Atameh was a poet famous for his writings on cooking and food. Thus his name Atameh. He was a contemporary of Shah Nimatullah Wali and met him several times. He was born in Shiraz and is burried there. His divan has survived.

Nasimi

Alī ‘Imādu d-Dīn Nasīmī, often known as Nesimi, born probably in 1369 was an Azerbaijani poet. Known mostly by his pen name of Nesîmî. He composed one divan in Azerbaijani, one in Persian, and a number of poems in Arabic. He is considered one of the greatest Turkic mystical poets of the late 14th and early 15th centuries and one of the most prominent early divan masters in Turkic literary history.

Very little is known for certain about Nesîmî’s life, including his real name. Nasîmî’s birthplace, like his real name, is wrapped in mystery too: it is believed he was born in a province called Nasîm located either near Aleppo in modern-day Syria (or Iraq).

From his poetry, it’s evident that Nasîmî was an adherent of the Ḥurūfī movement, which was founded by Nasîmî’s teacher Fażlullāh Astarābādī of Astarābād, who was condemned for heresy and executed in Alinja near Nakhchivan. Nasîmî became one of the most influential advocates of the Ḥurūfī doctrine and the movement’s ideas were spread to a large extent through his poetry.

Around 1417, as a direct result of his beliefs — which were considered blasphemous by the religious authorities — Nasîmî was seized and, according to most accounts, skinned alive in Aleppo.

Jami

Nur ad-Din Abd ar-Rahman Jami Jāmī (born August 18, 1414 -November 17, 1492), is known for his achievements as a scholar, mystic, writer, composer of numerous lyrics and idylls, historian, and one of the greatest Persian and Sufi poets of the 15th century. Jami was primarily a outstanding poet-theologian of the school of Ibn Arabī and a prominent Sũfī. He was recognized for his eloquent tongue and ready at repartee who analyzed the idea of the metaphysics of mercy. Among his famous poetical works are: Haft Awrang, Tuhfat al-Ahrar, Layla wa -Majnun, Fatihat al-Shabab, Lawa’ih, Al-Durrah al-Fakhirah.

Jami was born in Kharjerd in central Khorasan. Originally his father had come from Dasht, a small town in the district of Isfahan and Jami’s early pen name was Dashti. A few years after his birth, his family migrated to the cultural city of Herat where he was able to study Peripateticism, mathematics, Arabic literature, natural sciences, language, logic, rhetoric and Islamic philosophy at the Nizamiyyah University of Herat. While in Herat, Jami was a central role and function of the Timurid court, involved in the politics, economics, philosophy, religion, and Persian culture. He later went to Samarkand, the most important center of scientific studies in the Muslim world and completed his studies there. He was a follower of the Naqshbandi Sufi Order. He also embarked on a pilgrimage that greatly enhanced his reputation and further solidified his importance through the Persian world.

Navaii

Nizām-al-Din ʿAlī-Shīr Herawī (9 February 1441 – 3 January 1501) was a politician, mystic, linguist, painter, and poet of Uyghur origin who was born and lived in Herat. He is generally known by his pen name Navā’ī (meaning “melodic” or “melody maker”). Because of his distinguished Chagatai poetry, he is considered by many throughout the Turkic-speaking world to be the founder of early Turkic literature.

Mīr Alī Shīr was born in 1441 in Herat, which is now in northwestern Afghanistan. He belonged to the Chagatai amir class of the Timurid elite. His father died while Mīr Alī Shīr was young, and the ruler of Khorasan, Babur Ibn-Baysunkur, adopted guardianship of the young man. He was subsequently educated in Mashhad, Herat, and Samarkand.

Under the pen name Navā’i, Mīr Alī Shīr was among the key writers who revolutionized the literary use of the Turkic languages. Navā’ī himself wrote primarily in the Chagatai language and produced 30 works over a period of 30 years, during which Chagatai became accepted as a prestigious and well-respected literary language. Navā’i also wrote in Persian (under the pen name Fāni), and to a much lesser degree in Arabic and Hindi.

Mohtasham Kashani

Kamāl-al-Din Mohtasham Kāšāni (1528–1588) was a Persian poet of Safavid’s period. He is mainly known by his elegy on martyrdom of Imam Hossein and his family. he was a follower of the shiite school of “voghoo” and one of the most well known of shiite poets. He was born in Kashan and is burried there.

Sheikh Bahaii

Bahāʾ al‐Dīn Muḥammad ibn Ḥusayn al‐Āmilī (also known as Shaykh‐i Bahāʾī), (1547 – 1621) was a scholar, philosopher, architect, mathematician, astronomer and a poet in 16th-century Iran. He was born in Baalbek, Lebanon. He lived in Jabal Amel in a village called Jaba. Jabal Amel had always been one of the main Shiite centers of west Asia. Even today various Shiite groups live there. They have played an important role in establishing Shiism in Iran, especially from 13th century onwards. The Baha’i (Bahaei) progeny was among those well-known Shiite families. He immigrated in his childhood to Safavid Iran with his father. He is considered one of the main co-founders of Isfahan School of Islamic Philosophy. In later years he became one of the teachers of Mulla Sadra.

He wrote over 88 books in different topics mostly in Persian but also in Arabic. His works include Naqsh-e Jahan Square in Isfahan, as well as designing the construction of the Manar Jonban, also known as the two shaking minarets, situated on either side of the mausoleum of Amoo Abdollah Garladani in the west of Isfahan. Shaykh Baha’ al-Din was also an adept of mysticism. During his travels he dressed like a Dervish and frequented Sufi circles He also appears in the chain of both the Nurbakhshi and Ni’matullāhī Sufi orders. His Persian poetry is also replete with mystical allusions and symbols. He is buried in Imam Reza’s shrine in Mashad in Iran.

Vahshi Bafghi

Kamal al-din (or Shams al-Din Mohammad) known by his pen name Vahshi Bafghi was a Persian poet of the Safavid period. Vahshi was born in the agricultural town of Bafq, southeast of Yazd. Vahshi was educated in the town of Yazd before moving to Kashan which was a center of literary activity in the Safavid period. He worked as a school teacher before his poetry attracted the attention of the regional governors. From then on his career was one of serving the courts of various regional governors as well as Safavid Rulers.

Vahshi’s, Farhad and Shirin, a Persian folklore and romantic story of Sassanid Iran is written in the meter of the Persian poet Nizami’s romantic epic Farhad and Shirin. Although the work was left unfinished at the time of Vahshi’s death, with the introduction and barely 500 verses of the story completed, it has been recognized as one of the poets most famous masterpieces.

Vahshi according to one account was said to have died in 1583 at the age of 52 in Yazd. He was buried in this city.

Mir Razi Artimani

Mir Razi Artimani was a famous Safavid poet and mysticborn in Artiman, Tusarkan. He died there and his tomb is still a place of pilgrimage. The famous saghi nameh is his work. He was a student of Mir Morshed Broojerdi.

Saeb Tabrizi

Ṣāʾeb Tabrizi, (Mīrzā Muḥammad ʿalī Ṣāeb, 1601/02-1677) also called Saeib Isfahani was a Persian poet and one of the greatest masters of a form of classical Persian lyric poetry characterized by rhymed couplets, known as the ghazal. In addition to his Persian works, Ṣāʾeb Tabrīzī also wrote poems in his native Azeri.

Ṣaeb was born and educated in the city of Eṣfahān and in about 1626 he traveled to India, where he was received into the court of Shāh Jahān. He stayed for a time in Kabul and in Kashmir, returning home after several years abroad. After his return, Shāh ʿAbbas II, bestowed upon him the title King of Poets.